kickstart.nvim

I was watching a thePrimegean video with TJ Devries and was curious who he was and what he had worked on.

I pulled up his youtube channel and discovered he works on Neovim… a lot.

Since I have been practicing Vim recently with the goal of adopting it fully for programming, I watched some of his videos.

He had one on getting up and running with Neovim from 5 months ago which showed how to quickly get started using kickstart.nvim.

kickstart is just a boilerplate configuration meant to be extended and changed later.

Since neovim scripting is written in lua, I hopped over to https://learnxinyminutes.com/ to quickly get a hang of the syntax and features.

Here were my main notes:

multiLineStr = [[example

multi

line

string]]

deleteThisVarInMem = nil

while n < 10 do

num = num + 1 -- lacks ++ and +=

end

if n > 40 then

print('yo')

elseif s ~= 'wut' then --as in not equals like !=

else

local blah = io.read() -- local scoped from stdin

end

karlSum = 0

for i = 1, 100 do -- The range includes both ends.

karlSum = karlSum + i

end

-- Another loop construct:

repeat

print('the way of the future')

num = num - 1

until num == 0

function fib(n)

if n < 2 then return 1 end

return fib(n - 2) + fib(n - 1)

end

-- Calls with one string param don't need parens:

print 'hello' -- Works fine.

-- Dict literals have string keys by default:

t = {key1 = 'value1', key2 = false}

-- String keys can use js-like dot notation:

print(t.key1) -- Prints 'value1'.

t.newKey = {} -- Adds a new key/value pair.

t.key2 = nil -- Removes key2 from the table.

-- Literal notation for any (non-nil) value as key:

u = {['@!#'] = 'qbert', [{}] = 1729, [6.28] = 'tau'}

print(u[6.28]) -- prints "tau"

for key, val in pairs(u) do -- Table iteration.

print(key, val)

end

-- _G is a special table of all globals.

print(_G['_G'] == _G) -- Prints 'true'.

-- There are only tables, no classes or lists

-- {1,2,3} is like a list. Indexes also follow that pattern

-- Here is a "class"

Dog = {} -- 1.

function Dog:new() -- 2.

newObj = {sound = 'woof'} -- 3.

self.__index = self -- 4.

return setmetatable(newObj, self) -- 5.

end

function Dog:makeSound() -- 6.

print('I say ' .. self.sound)

end

mrDog = Dog:new() -- 7.

mrDog:makeSound() -- 'I say woof' -- 8.

-- Suppose the file mod.lua looks like this:

local M = {}

local function sayMyName()

print('Hrunkner')

end

function M.sayHello()

print('Why hello there')

sayMyName()

end

return M

-- Another file can use mod.lua's functionality:

local mod = require('mod') -- Run the file mod.lua.

-- require is the standard way to include modules.

-- require acts like: (if not cached; see below)

local mod = (function ()

<contents of mod.lua>

end)()

-- It's like mod.lua is a function body, so that

-- locals inside mod.lua are invisible outside it.

-- This works because mod here = M in mod.lua:

mod.sayHello() -- Prints: Why hello there Hrunkner

-- This is wrong; sayMyName only exists in mod.lua:

mod.sayMyName() -- error

-- require's return values are cached so a file is

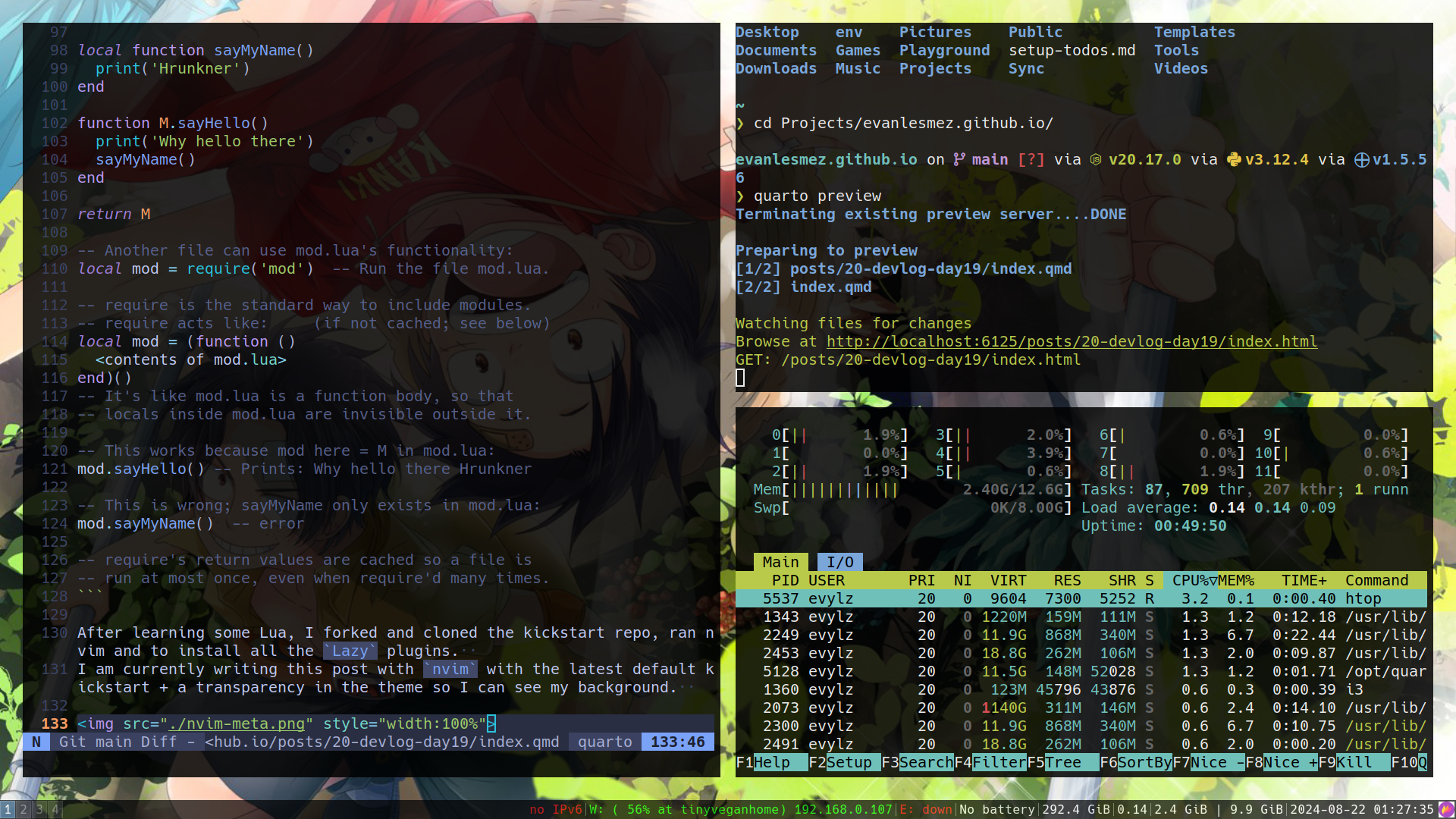

-- run at most once, even when require'd many times.After learning some Lua, I forked and cloned the kickstart repo, ran nvim and to install all the Lazy plugins.

I am currently writing this post with nvim with the latest default kickstart + a transparency in the theme so I can see my background.

Godot

Learned about layers and masks for collision objects.

Layers and masks are numbered and selectable in the CollisionObject2D node properties.

The selected layer numbers group objects into sections they can be detected on.

The mask numbers determine which layers can be detected by the object.

For example: Layers 1 and 2 are selected for an object with mask 3.

Other objects can detect this object if they have mask 1 or 2.

Other objects with layer 3 are detected by the example object.

This is useful when you want some items to have collision interactions but not with others which happens literally all the time in every game ever.

Thanks for reading!